2021’s Most Pressing (Yet Promising) Waste Challenges

Reflections on Circular Economy at GreenBiz21

At the beginning of February, I attended GreenBiz 21, GreenBiz’s annual conference about sustainability and business. As someone who’s admittedly fascinated by waste (and agrees that waste problems are often some of our stupidest problems), I focused specifically on the circular economy track of breakout sessions. A few things stuck out to me that reflect some of 2021’s most pressing waste challenges, as well as some of the hopeful progress made over the last few years.

There is demand for recycled plastics--but the domestic market is struggling to keep up with supply.

The good news: groups like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy Global Commitment have led these companies in setting and working towards ambitious targets towards using more recycled content and ensuring their products are recyclable. The bad news: currently, the supply of recycled plastics can only meet 6% of demand in the U.S. in Canada, and given the number of companies that have made recycled content commitments, demand is only anticipated to rise. The 450+ signatories to the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment represent 20% of all plastic packaging produced globally. To achieve their 2025 targets for recycled content, these companies will need to source 6 million tonnes a year of recycled material, compared to just the 1.5 million tonnes required in 2019. This demand represents an enormous gap that producers of recycled plastic will need to fill. Meanwhile, the issue has only been made worse by the dropoff in recycling that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as from the low price of oil, the key input in virgin plastics, which has made virgin plastics cheaper to use than recycled plastics.

These issues, as well as a constant fight against contamination in recycling plants, threaten the already precarious plastics recycling industry, which continues to face a lack of investment and public sector support. During one panel, Steve Sikra, of the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, mentioned how the Alliance is needing to invest in more infrastructure to create usable post-consumer resin (PCR), with the goal of helping to make plastic waste a commodity. He also mentioned the necessity of chemical recycling to achieve this goal, in contrast to the traditional mechanical recycling that most plants use today.

Companies are thinking more holistically about the business case for circularity...

During the panel about the business case for circularity, Jennifer Keesson of IKEA explained how the company launched a buyback program in select countries to take back used furniture to reduce waste and prolong products’ lives. Ken Voeller of REI explained a similar “recommerce” initiative the co-op launched in 2018 to sell used gear, as well as their expanding gear rental program, both of which aim to increase the lifespan of REI products. Naturally, many attendees’ first question was how these programs stack up financially to only selling new products--is IKEA able to make a profit from used products after taking on the costs of refurbishing and reselling? Followed by: does REI worry they’ll cannibalize their own business if they offer customers cheaper, used products? The answer to the first question is that we don’t yet know--these buyback programs are recent enough that it’s challenging to say if they’re increasing profits.

Surprisingly, though, the second question may be a bit easier to answer. Panelists explained that every company worries about cannibalization, but they generally find customers tend to add used products onto purchases of new items, rather than replace all their shopping for new products with used items. (From a business standpoint, this sounds great, though from a sustainability perspective, it is fair to then ask--are these programs just playing into our tendency to over-consume?) Furthermore, Voeller pointed out that REI has been looking beyond the absolute sales numbers from new versus used products to understand the business case for circularity. Instead, they are attempting to quantify the second-order effects of these programs--for example, how many new customers are attracted to REI because of the availability of a cheaper price point? How many customers are retained who might not have been before? How many customers are trying new outdoor activities because they have the option to rent the gear, rather than buy? As consumer businesses experiment with buy-back and rental models, these questions will become all the more important in the quest for circularity.

...and they’re connecting the dots between circularity and climate goals.

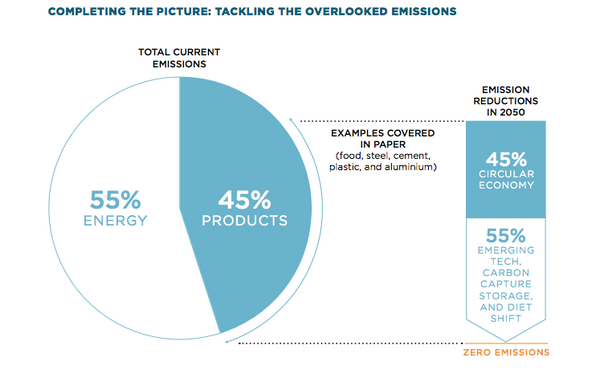

Soukeyna Gueye, a Project Manager for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, brought up what I think is the key statistic all circularity practitioners should be constantly repeating: switching all of our energy to renewables will only get us 55% of the way toward limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius as set out in the Paris Agreement; the remaining 45% comes from how we make and use products, as well as how we grow food. The myriad efforts that fall under “working towards a circular economy” contribute to that 45%. As many companies have set ambitious climate goals to address their emissions, many -- especially those that make “stuff” -- quickly found that their waste reduction goals are not extraneous to their climate goals -- they’re paramount to them. Markus Pfanner of Tetra Pak and Jason Blake of PepsiCo both explained how their companies have taken more integrated approaches to their climate and waste goals.

Why do I fixate on this point? I’ve found that when I tell friends I’m pursuing a career in plastic waste reduction, they ask me what happened to my interest in climate change. The inseparable relationship between waste--especially plastic--and climate change is undeniable but perhaps harder to visualize than the direct relationship between, say, an internal combustion engine’s pollution of CO2 into the air. But the making of stuff and the disposal of stuff (not to mention the packaging for that stuff) uses energy and therefore produces greenhouse gas emissions just like cars do. Take, for instance, the fact that 99% of plastics are derived from fossil fuels, and that the creation of plastics alone makes up a substantial amount of our fossil fuel diet--by 2050, the emissions from plastics could represent 10-13% of our remaining carbon budget. This doesn’t even account for the emissions plastics spew at the end of their lives as they are incinerated, or as they emit methane in the oceans.

If I could summarize my views on the circular economy, as well as my aspirations for how discussions about circular economy go, I’d use the word nuanced. I always feel a bit more hopeful coming out of these discussions when they are nuanced enough to acknowledge that there exists no silver bullet for addressing our waste woes, but also thoughtful enough to tie our circular economy goals to the climate targets we know we must meet. This year’s GreenBiz lived up to my expectation (as most things from GreenBiz often do) of exploring the subtleties of the challenges in circular economy, as well as showing the role that creative business strategy can have in advancing it.