Barriers and Solutions to Low and Moderate-Income Solar Adoption

Residential solar power in the U.S. has grown rapidly in the last decade, from around 23,000 homes in 2006 to over 920,000 by the end of 2015.[1] This number has continued to rise, making rooftop solar systems available to more and more homeowners who are interested in reducing their electricity bills and mitigating their impacts on climate change.

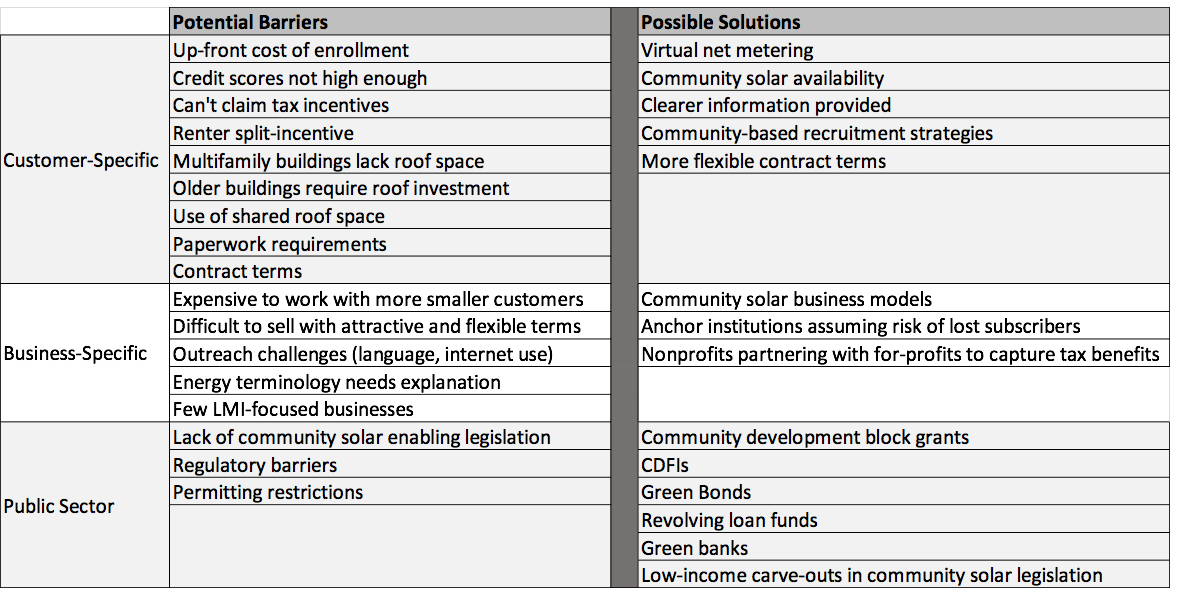

However, many constraints prevent low- and moderate-income (LMI) households from installing rooftop solar systems. In a new research project based at Yale, we are testing solar uptake strategies focused on LMI communities. As part of this research, we have been studying the barriers that prevent low-income families in the U.S. from adopting solar and the solutions that may help families overcome these barriers. This post highlights the key barriers and solutions we have identified, summarized in the table below.

Barriers to Increased LMI Solar Adoption

Customer-Specific Barriers

Lower-income households face several financing barriers. First, they are often less able to afford the upfront cost of a solar contract. Second, individuals’ credit scores also may not meet requirements set by rooftop solar developers or financing companies. Third, low-income customers with low tax bills cannot claim tax incentives for solar projects. And fourth, many lower-income individuals are more likely to rent their homes, creating a split incentive where the owner, who would pay for the installation, does not see the benefits of reduced electric bills.

In addition to financial limitations, some customers have physical constraints, such as those who live in multifamily buildings without enough roof space for each family to install solar. Many also live in older buildings whose roofs require repair to support panel installation.

Other barriers include divergent customer preferences, such as potential disagreement in a multifamily structure over whether to use a roof for solar or another purpose. While community solar programs, which remotely sell portions of solar farms to households, may mitigate some physical impediments, one report found in interviews with providers that customers find the paperwork intimidating; another found greater customer uptake after making the contract term shorter and cheaper.

Business Specific Barriers

Meanwhile, solar companies can face a number of challenges serving LMI customers. As with the broader residential solar market, selling solar to many individual customers is more expensive than working with a single large buyer. LMI customers prefer flexible terms when subscribing to community solar; but flexible contracts often incur raised rates to compensate for the risk of subscriber turnover. This ultimately discourages potential customers.

U.S. solar companies may also struggle with outreach to low-income individuals, as LMI households often have time constraints that make it harder for them to learn about purchasing solar. In other cases, language is a barrier,[2] requiring multilingual marketing materials. Some low-income individuals report less internet usage than people with higher income,[3] which restricts the number of marketing channels for companies. Additionally, one report explains that marketing materials use energy terminology that is less familiar to residents, making it harder to explain the benefits of solar. Finally, a broader barrier commonly cited is that there are simply not enough solar organizations targeting LMI households.

Public Sector Barriers

A few reports identify policy and administrative barriers that can limit successful outreach. Many states lack community solar enabling legislation, which can inhibit development of affordable or shared solar projects, while other states may have regulatory barriers that restrict where or how an LMI individual can invest in residential solar. In addition, states or municipalities may have permitting restrictions that impede the ability of individuals to acquire rooftop solar. (Connecticut has mapped restrictions here.)

Possible Solutions to Bolster LMI Solar Demand

To overcome these barriers, businesses and governments can support tailored business models that address upfront costs, enhance customer awareness, and improve customer engagement.

Customer Focused Solutions

Virtual net metering allows customers to deduct the cost of a portion of their electricity bill in exchange for investment in remotely generated solar power, foregoing solar panel installation directly on their property. California piloted a virtual net metering tariff for participants in the state’s Multifamily Affordable Solar Housing program. Community solar or shared solar projects similarly relieve customers of the need for suitable property, and can reduce the upfront enrollment costs for customers by utilizing solar subsidies, economies of scale, and enrollment of anchor tenants to reduce the risk of default.

Companies can also improve their customer engagement by increasing the clarity and simplicity of their marketing materials. Community-based recruitment strategies and educating people on solar contract options help as well.

In addition, the demographic designation “LMI” encompasses a range of incomes and households, and there is a wide range of credit scores throughout the demographic. Therefore, effective programs for LMI outreach may be best structured with flexible strategies to reach different segments within LMI populations.

Business Focused Solutions

Community solar programs that offer flexible contract periods, zero or low upfront enrollment costs, and involve collaboration with utilities or mission driven organizations could reach LMI communities more effectively and cheaply. “Anchor institutions” can sponsor community solar projects, which would offset some of the risk of low-income subscribers potentially missing payments or dropping their contracts. Innovative contracts that limit upfront contract enrollment costs can avoid deterring customers who lack the necessary cash on hand to enroll in traditional solar contracts.

Nonprofit organizations seeking to promote LMI enrollment in community solar projects can also consider working with private partners to fund solar projects. Nonprofits are unlikely to either generate sufficient revenue or carry a tax liability that would allow them to benefit from tax credits. To capture the full value of tax incentives, nonprofits must partner with a tax-paying entity.

Public Sector Focused Solutions

Finally, states and municipalities can help increase LMI access to residential solar projects. Public financing tools such as Community Development Block Grants, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), green bonds, revolving loan funds, and green banks can help solar companies access lower-cost capital to increase the affordability of residential solar power in LMI communities. Community solar carve-outs that reserve a percentage of solar power for low-income subscribers can also provide more affordable solar access. Plus, streamlining the permitting process and allowing virtual net metering can reduce additional barriers.

In conclusion, although state and local programs in recent years have attempted to encourage LMI households to participate in residential solar programs, it is clear that numerous systemic barriers continue to impede LMI solar adoption. This research aims to identify more effective outreach strategies and provide insight into the best ways to help lower-income households participate in the solar revolution. That way, companies can better engage potential LMI customers and ensure the residential solar market is inclusive for all communities.

[1] https://emp.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/tracking_the_sun_ix_report.pdf based on p10 table at an 85% factor

[2] This analysis of 2013 Census Bureau data showed that 25% of low-english proficiency households live below the poverty line, as compared to 14% of english-proficient households.

[3] This Pew study in 2015 showed that adults in households earning under $30,000 per year reported the least amount of internet usage (74% use the internet, compared to 85-97% of adults in higher brackets).

Photo credit: ‘Low Income Solar Policy Guide’ produced by GRID Alternatives, Vote Solar and Center for Social Inclusion